Four factors loom large in illnesses when you’re hiking — poor judgment, inclement weather, inadequate clothing, and faulty gear.

Recently, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention ranked hiking as the third most dangerous outdoor recreational activity, based on injuries reported by 63 U.S. hospitals.

While hiking comprises just 6.3 percent of all outdoor sports and recreational accidents, as published in Wilderness and Environmental Medicine, it’s worth knowing that many of these ailments can be prevented. Poor weather, inadequate clothing, and faulty gear contribute to many trail illnesses.

The best advice for healthy hiking? With weather—don’t push your luck. An experienced leader, faced with bad weather, knows when to turn back, even short of a goal. This includes heavy winds, rain, lightning, and blizzards.

Update and maintain your equipment. This includes clothing, shelter, stoves, and boots. Always match your equipment list to the terrain and environment you’ll be hiking through.

The following five conditions can turn a trip of a lifetime into a fight for your life. All of them are more easily prevented than cured, and all of them are potentially fatal medical emergencies. Simple planning and “being prepared” can turn the odds in your favor.

DEHYDRATION

Most people equate dehydration with hot weather and heat-related ailments such as heat stroke. Dehydration can also contribute to hypothermia and altitude sickness. In fact, drinking enough water is probably the No. 1 way to keep you healthy—in cold and hot weather.

Prevention: Never skimp on water. Drink as much as you can before you start hiking, and continue drinking regularly. Use maps, guidebooks, and current local information from rangers to find out where the water sources are and how reliable they are. In dry or desert environments, drink at every water source and carry extra water so you won’t go dry. In cold weather, cook up hot drinks to make hydration more appealing.

Symptoms: Thirst, dark-yellow urine, dizziness, headaches, nausea and vomiting, and—later—unconsciousness.

Treatment: Cool down, rest, and drink. Use electrolyte-replacement drinks or a homemade version consisting of a tablespoon of sugar and a half teaspoon of salt in a liter of water.

HEAT EXHAUSTION

Closely related to dehydration are heat exhaustion and heat stroke.

Prevention: Drink often, take plenty of shade breaks, don’t push too hard, walk in cooler parts of the day, take advantage of streams and lakes for a quick temperature-reducing dip, and, on a long hike, take it easy until your body has had time to acclimate to heat. Wear well-ventilated clothing that covers your skin.

Symptoms: Dizziness, light-headedness, confusion. Heat exhaustion victims will be sweaty and clammy. In heat stroke, victims will be flushed but dry and hot to the touch. Heat stroke symptoms also include fever, seizures, rapid heartbeat, and loss of consciousness.

Treatment: Place the victim in the shade, covered with water or with towels and clothes soaked in cool water. Treat for shock. Administer water or electrolyte-replacement drinks, and seek medical attention.

HYPOTHERMIA

Hypothermia, an insidious threat, often goes unrecognized until it becomes an emergency. You don’t have to experience snow camping in Siberia to be at risk. Hiking on a 50-degree day with occasional rain showers or rafting on a cold river can be equally dangerous.

Prevention: Drink frequently, even if you don’t feel thirsty. Check your gear (hats and gloves, especially). Note early signs of chill, such as shivering, and reduce or eliminate your exposure immediately, especially in wet conditions. Drink hot liquids or build a fire.

Symptoms: The “umbles” (stumbles, mumbles, fumbles, grumbles). Shivering stops, but the body temperature is cold. Also, fatigue, forgetfulness, irrationality, staggering, and unconsciousness.

Treatment: Eliminate exposure (put up a tent, get out of the elements, sit on an insulating pad, get into a sleeping bag), make a hot drink, and gently warm the victim. Hikers are far more successful at preventing hypothermia outdoors than curing it. A severe case will require an emergency rescue evacuation.

HIGH-ALTITUDE SICKNESS

Altitude sickness is a result of traveling or climbing too high too fast: The body doesn’t have time to adjust, and symptoms progress from a headache to life-threatening edemas (swelling of the lungs and brain). Altitude sickness strikes different people at different elevations, but most people feel some effects at elevations above 10,000 feet.

Prevention: Hike high, camp low. Hiking higher exposes your body to the new elevation; camping low lets you adjust to it. On climbs where this is not possible, limit your net elevation gain to no more than 1,000 feet per day (once you’re above 10,000 feet). The drugs Diamox and, believe it or not, Viagra are commonly used to help prevent high-altitude sickness. They must be prescribed by a physician and taken as directed.

Symptoms: Above 10,000 feet, assume that any unusual symptoms are the result of altitude. Common early symptoms are loss of breath, headaches, sluggishness, loss of appetite, and nausea. More serious symptoms include disorientation, staggering, irrationality, loss of balance, and, finally, pulmonary and cerebral edemas.

Treatment: Treat the early symptoms and you won’t have to deal with the later ones. You can wait out the minor symptoms and see if you acclimate—many people do—after taking a rest day. If symptoms persist or worsen, returning to a lower elevation is the only treatment.

HYPONATREMIA

Ironically, this condition can occur in the same hot weather that causes heat-related illnesses. Drinking too much water, often in conjunction with excessive sweating, causes hyponatremia. Sweating causes the loss of salts and electrolytes. The imbalance makes it impossible for the body to properly function. Untreated, a serious case can lead to kidney (and other organ) failure.

Prevention: Scale it down a notch. In hot weather, cut back your mileage and pace and take plenty of rests. Most important: Snack frequently, whether you’re hungry or not, to replace the electrolytes. One of the best snacks is a handful of mixed nuts, fruits, and banana chips, which contain salts, sugars, and potassium.

Symptoms: Early symptoms occur when you drink a lot but still experience persistent thirst. Other symptoms include urinating frequently, excessive sweating, nausea, vomiting, and headaches.

Treatment: A mild case of hyponatremia can be treated with rest, food, and electrolyte-replacement drinks. Sauces with salts replace the electrolytes. More severe cases require medical attention.

Kephart believed that expert skills and appropriate gear were the keys to comfort in the wild outdoors. And you should never be miserable on a camping trip, either. So here are some tips for camping in comfort.

Protect the Head

Bring more hats than you think you’ll need. These three will keep you prepared for any weather: a broad-brimmed canvas hat (preferred) or ball cap for sun, a wool stocking cap for cold, and a waterproof “sou’wester” for rain. In cold weather, bring along a wool balaclava for use as a neck warmer and/or sleeping helmet.

Buy Clothes Big

Long-sleeved shirts and sweaters should be a full size larger than your city clothes. Rain jackets and shells should be larger still, and cut full—like an Inuit winter parka—so that they will fit over bulky clothes. Sleeves should be wide for ease of movement. Zippers should close high on the neck so icy air can’t chill your chest; most parkas leave a gap at the throat when they’re zipped up. And, more often than not, underarm zippers will leak in heavy rain—even those claiming to be waterproof.

Nix the Rain Pants

The zippered ankle closures don’t keep out rain—they just restrict ventilation and make you sweat (primitive man learned long ago that water doesn’t flow uphill). Plus, the zippers jam with debris and often fail. And the zippered legs can’t be shortened to fit short people. Avoid rain pants with wicking liners. When the liners get wet, they droop below the cuff and absorb water and wick it to your legs. They may also catch on vegetation and cause a fall.

Go With Wool

Always bring a long-sleeve wool shirt and lightweight long johns, even in the summer. Wool has a greater temperature comfort range versus synthetics. It’s more breathable, and it doesn’t develop obnoxious odors. If you think you’re allergic to wool, you haven’t tried Merino wool from Australia and New Zealand. Tip: You can shrink-fit military surplus woolens to fit small kids if you cook the woolens in boiling water for five minutes and then dry them with high heat. For centuries lobster fishermen used this “shrink-fit” procedure to make their woolens water-resistant.

Mix Fabrics

While you might get by with a cotton T-shirt, a synthetic fabric (such as Dry-Fit) will help keep you cool during summer. But socks, no matter the season, should always be nearly pure wool. Trousers may be nylon, polyester, cotton-polyester, or a mix of these fabrics. Shorts and sunburn go hand-in-hand. Do not wear blue jeans except for day hikes in perfect weather.

Jacket for Windy Weather

Everyone should have a breathable nylon wind shell for dry, blustery days outdoors. Wear the wind shell for gusty weather and save your rain gear for rain. Why? Because any garment that is worn too much will soon develop holes. Store rain clothes in a protective fabric sack in your pack.

Sit When Possible

Camp chores—cooking, washing dishes, tending the fire—go easier when you don’t sit on the ground. So, bring a folding stool. One variety has a backrest and zippered storage pouch, and it sits on two parallel aluminum rails that won’t sink into the ground. When not in use, it folds flat and clips (with bungee cords) to a pack. When weight is a concern, nix the stool and bring a square of closed-cell foam.

Cover the Hands

Wear wool gloves with rubber traction dots for cold and neoprene gloves for rain. Winter trips demand both gloves and mittens.

Keep It Personal

Everyone should have a personal supply of adhesive bandages, aspirin, soap, and hand cream in case the first-aid kit is inaccessible (perhaps in a leader’s pack).

Each person should take responsibility for small cuts that can become infected if they’re not washed and quickly bandaged. Frequent use of hand cream will deter cracked skin. And how can you freshen up during the day if your toothbrush and soap are packed away?

Many Scouts don’t have the latest gear. But they often camp more comfortably than non-Scouts who do. Why? Because Boy Scouting takes its motto seriously: Be Prepared.

Hammock camping is taking Scouting by storm. More and more troops are integrating them into regular monthly outings and sightings at high-profile events such as recent world and national jamborees.

But what is hammock camping all about, and should your troop really take it seriously? Are hammocks really that great? Most folks are convinced only after they get a chance to lay in a hammock, but until that opportunity comes, here are my top 10 reasons to consider hammock camping:

10. It’s affordable! Hammocks are some of the simplest shelters around and have been used for centuries. A basic hammock costs as little as $20, and models with integrated bug nets (e.g., “jungle hammocks”), can be found for $60. Our Scout troop chose to make their own hammocks, complete with zippered bug netting and inexpensive tarps, for $30 a piece. High-end commercial camping hammocks, complete with tarp and bug netting, are still reasonable at $100.

9. It’s lightweight. A fully decked-out camping hammock, complete with zippered bug netting and a tarp, can weigh as little as 30 ounces. Creative hangers have gone sub-ultralight with hammock set-ups as light as 13 ounces.

8. It’s packable. Unless you’re tarp camping, most Boy Scout backpacking tents are bulky. Splitting up poles, rain fly, and tent body help distribute the mass, but they still take up a lot of room. Most camping hammocks stuff down to the size of small cantaloupe. An 8-foot by 10-foot tarp can fold down flat and tight, freeing up room and reducing weight.

7. It’s refreshing! At a summer camp in West Virginia, I remember being cooped up in a dome tent desperately seeking ventilation. Even with all the doors, vents, and windows open, there was little I could do to cool off. Hammocks, by comparison, are built specifically for hot, muggy climates. With 360-degree air circulation, hammocks are the perfect summer accommodation with superior ventilation, convective cooling, and air flow. Fast-drying nylon camping hammocks can even be sprayed with water for refreshing evaporative cooling.

A sample of the illustration guide in “The Ultimate Hang.”

6. You can still use your regular sleeping bag and pad. A hammock doesn’t replace the need for adequate insulation, but you don’t need to spend a fortune to stay warm. You can use the same bedding from a tent, including a good sleeping bag and insulated pad (closed-cell foam or self-inflating). With the right insulation, you can hammock camp year round.

5. It reinforces and supports the Youth Protection guidelines. Hammocks are designed for single-occpancy, providing separate accommodations in a private, bug-free enclosure. Privacy for the youth is promoted with a fully-enclosed, individual shelter where the Scout can change clothes and be protected.

4. It’s Leave No Trace friendly. Hammocks can be set up in impact-resistant places where tents cannot comfortably go, such as over boulders and rock fields. Hammocks are also suspended above the ground, which reduces trampling at a camp site. In addition, the ground no longer needs to be cleared of rocks, twigs, or other offending discomforts, leaving a site in a more pristine condition. And with protective webbing straps, trees are protected from strangulation and scarring.

3. It gets you off the rocks, roots, bugs, muck, and slope of the ground. Speaking of discomforts, hammocks hang above them all. You no longer have to find a level spot and you can avoid the unpleasant routine of scraping the tent floor of gunk and drying out the tent before packing. Hammocks can be pitched without ever touching the ground, and mildew-resistant nylon hammock tarps can be packed separately when they get wet.

Image courtesy of Grand Trunk.

2. It makes camping exciting! Scouts love hammock camping—it’s just plain fun! No matter how many times I bring hammocks on camping trips, they seem to maintain their novelty and attraction with the boys. When I started up with a new troop in Arizona, I noticed that several boys and leaders had a certain apathy toward camping, but after introducing hammocks, their interest was piqued. I used a hammock during our 50-mile backpacking trip and afterwards the Scouts were begging to get their own. During subsequent troop meetings, we sewed up hammocks for each Scout. Now, both youth and adult Scouters ask about upcoming camping trips and whether or not we can bring hammocks.

1. It’s incredibly comfortable. The number-one reason Scouts should use hammocks camping is because hammocks are extremely comfortable. No more rocks and roots in your back, and no more sliding on uneven ground. Scientific research confirms that the gentle rocking motion contributes to deeper, more fulfilling sleep. During long-term resident camping, hammocks provide a cozy bed you can look forward to night after night.

MAKING YOUR OWN dehydrated snacks and meals require a little advance planning and preparation, but the reward of enjoying great-tasting and nutritious food on the trail makes it all worthwhile.

For weekend backpacking trips, you can dehydrate and pack all your food during the week before the trip. For a weeklong trip, start drying the food two weeks before you depart. You can’t leave it to the last minute! Getting it done early will give you peace of mind knowing your food supply is all set.

Most of the action involved in dehydrating food takes place inside the dehydrator. It takes less than an hour to cut up fruits and steam vegetables. Once you put the food in the dehydrator, the machine will quietly do the work while you sleep or go to work or school. A timer that automatically shuts off the machine after the programmed amount of time is a valuable feature to look for in a dehydrator. Appliance-grade timers can also be purchased separately if your dehydrator doesn’t have one.

Start with a Menu

Write up a menu for each day of your trip. This will include breakfast, lunch, dinner, four to five snacks and a dessert for dinner. Plain water is the easiest beverage to consume on the trail, but if you want flavored drinks there are plenty of powdered drink mix products available. Pack these in individual servings.

Snacks

Snacks might include individual servings of trail mix, nuts, Goldfish and dried fruit. Make a list of the dried fruits you would like to eat. Apples, pears and bananas are three favorites. A good serving size is a half-cup of dried fruit, which is close to eating one and a half fresh apples, pears or bananas.

Break the Recipes Down Into Ingredients

Tally up all the ingredients from the recipes you plan to use to determine how much of each dried food you will need. Some items like macaroni, rice and oats you will simply purchase.

Dehydrate the Food

As you become more experienced with drying food, you will learn the quantity any type of food will yield when dried. To get you started, here is a list of the drying yields of common foods mentioned in this series.

How to start a fire in the woods, even when it’s wet.

One a bone-dry day or when there’s plenty of dry paper or fire-starter, anyone can make a fire. If the weather deteriorates to a persistent rain, they might get smoke. But that’s no guarantee they’ll get fire. Here’s how you can make a fire when the woods are wet with rain.

This method isn’t fast, but it works with any kind of wood—even damp wood. You’ll need a:

- Sharp knife. To split fine kindling, set the sharpened edge of the knife on the end of an upright piece of wood then pound the spine through with a thick stick. Use a folding knife with a secure lock so the blade won’t close on your hand when you pound on the spine.

- Folding saw.

- Small hatchet to use as a splitting wedge, never as a chopper.

First, collect your wood. Locate a dead, downed tree, out-of-sight of tents, trails, and waterways. Saw off an arm-thick limb. Touch the sawed end of the limb to your cheek (the center should feel dry). Don’t worry if there’s a ring of wet wood near the bark; you’ll discard it when you split the piece. Reject the wood if it smells damp or punky. The wood is good if it passes both cheek and smell tests.

Saw the limb into footlong sections and split each section into kindling. Note that the hatchet is used as a splitting wedge so there’s no chance of an accident.

Splitting wood is easier (and safer) with two people. Hold the hatchet with both hands and have a friend knock it through.

Hold the hatchet firmly with both hands and allow a friend with a log chunk to pound the hatchet head through.

Use that same procedure (with a lighter log) to split fine kindling with your knife. Then, use your knife to prepare your tinder. Cut a handful of wafer-thin shavings (Figure 2) from your dry splittings.

Now that you’ve reached the dry part of the wood splittings, slice off several wafer-thin shavings to use as tinder.

Assemble the tinder (a handful of dry wood shavings no thicker than a match), kindling (one-eighth to one-quarter-inch thick dry wood splittings), and fuel (quarter-split logs). Trim all bark and damp wood from your tinder and kindling, and separate your wood into piles—tinder, kindling, and fuel.

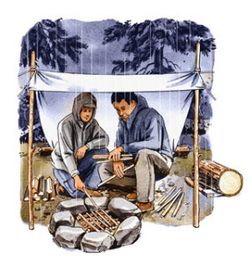

If it’s raining, work under a tarp so that all the materials stay dry.

Starter Accessories

- Carry a candle and chemical fire-starters.

- Cotton balls dipped in Vaseline, a flattened wax milk carton, and cigar-size newspaper logs that have been dipped into melted paraffin make good fire-starters. Don’t use loose newspaper pages; they absorb moisture on damp days.

- Make a “fire blower” as a bellows to nurse a developing flame by attaching a 6-inch piece of aluminum or copper tubing to a piece of rubber hose.

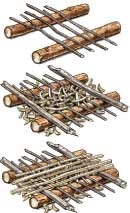

Once you have gathered the materials, build your fire from the ground up by following the four steps below.

Build It Right

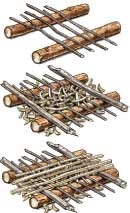

- Set two 1-inch-thick sticks about 6 inches apart on the ground (Figure 3, at right). Place four pencil-thin support sticks across the base. Space the support sticks about half an inch apart.

- Stack an inch-thick layer of wafer-thin shavings on top of the support sticks. Leave some space between each shaving to allow for airflow. Set two half-inch thick “bridge” sticks across each end of the base structure to support the heavier kindling you’ll add next.

- Place fine, split kindling across the support sticks. Splittings should be parallel to one another with plenty of space in between. They should not compress the tinder below.

- Apply your match directly underneath the tinder (shavings). When the first flame appears, hand feed shavings (not kindling) into the developing flame. Don’t add kindling until you have a reliable blaze. The raised firebase will produce a powerful draft that creates a bright, smoke-free flame.

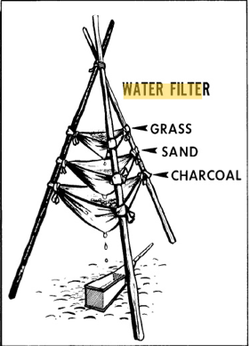

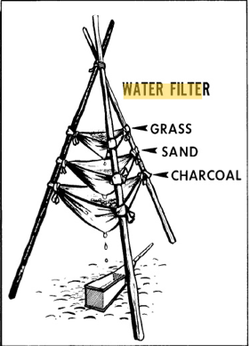

Everyone that spends time in the outdoors should have some sort of water filter in their kit. Whether it's a Sports Bottle type filter, a Canteen type filter, or at least a Survival Straw. There are far too many people that head out for a day trip, or a 3 day'er, and up on Search and Rescue's docket.

However, in a survival situation, a long term stint in the field, or after prolonged use, those filtration systems will stop working eventually. What then? What you need is the "know how" to build one of your own.

While it may not be the high tech 99.9% guaranteed microbial, and virus filter, it's pretty close if you do it right. Here is a drawing that will help you get the picture.

It is a simple concept, and it works great if you follow these instructions. Use plenty of grass to aerate the water in stage 1.

Try to wash the sand in a creek or stream first to get the loose dirt out, then fill the cloth just enough to not overload it once it is full of water, the sand in Stage 2 will remove all of the small debris that gets through stage one.

In Stage 3, use crushed charcoal made from your fire pit (not ashes, do some homework on how to make charcoal in a can) This stage helps to minimize both microbial and virus involvement.

Stage 4 is boiling the water if you can. Boiling is highly recommended. If you can't, this 3 Stage filter removes many of your problems, and greatly increases your chance of having a water supply you can trust.

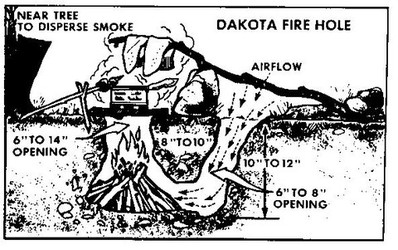

When it comes to surviving, or just being a proficient outdoorsmen, there is something significant about being the fire master. Fires serve many purposes, they are not just for cooking and keeping warm...Keeping your morale high, and maintaining your will to survive are pretty high on the list.

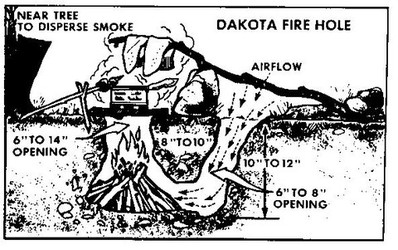

However, when you are trying to lay low (for whatever reason), and keep a tactical posture, fire can present its challenges due to the smoke it creates, giving away your location. Here is a great method of building a "low smoke - to no smoke" fire. It is called a Dakota Firepit, and it works really well in windy conditions too.

Yes, it works GREAT! To keep the smoke to a bare minimum, use small amounts of dry wood, a little at a time, and build up a strong bed of coals to cook on, or whatever. It is also helpful to build this under some strong tree cover to allow the trees to disperse what little smoke there is.

In spite of the best of intentions, during the winter months old Murphy can show up at anytime and throw you into a winter survival situation. Even though properly dressed for the outdoors, in order to survive a cold night you will need to start a fire.

When forced into winter survival mode you might ask yourself, "How would a twenty-first century woodsman start a fire in these conditions?"

Unfortunately, old man winter won’t come running to answer that question. And like thousands of people have found out over the centuries, when it comes to a winter survival situation, you're on your own when starting a fire.

Only planning, practice and advance preparation can get you through the cold and darkness.

This brings us to our next principle of winter survival: Fire is hardest to start when you need it the most.

Almost anyone can start a fire when its ninety degrees outside, the sun is shining and it hasn't rained for a couple of weeks. But, when you're cold, wet, hungry and thirsty, when everything around you is cold and wet, when your fingers are so numb you can barely feel your fingertips and the temperature is headed down; it’s then you discover if your fire making skills are up to the challenge.

Who can forget in the Jack London classic, To Build A Fire, where the main character struggles in vain to get a fire going at seventy-five below zero? Even though the story is considered fiction, it's a worthwhile read to get the proper mindset before you head into the wilderness.

Probably more than any other season of the year, winter survival requires that you develop the necessary self-reliance skills before an emergency arises.

There are many methods of fire starting available to the twenty-first century woodsman. Here is a list of twenty-five fire starting methods any outdoorsman can use.

These should be carried in your winter survival kit and be in your vehicle should you need them. These methods should also be practiced in all kinds of conditions before you need them.

Spark Based Fire

1. Flint and steel

2. Ferrocerrium rod

3. Butane lighter

4. Butane torch

5. Propane torch

Friction Based Fire

1. Bow drill

2. Hand drill

3. Pump drill

4. Rope drill

5. Crutch drill

6. Mouth drill

7. Fire thong hand drill

8. Polynesian fire plow

9. Aboriginal fire saw

10. Four person fire log

Heat Based Fire

1. Fire Piston

2. Magnifying lens (Glass lens, Fresnel lens, balloon, ice)

3. Concave lens or reflector (headlight or flashlight reflector, chocolate bar and soda can)

4. Nine-volt battery and fine steel wool

5. Car/atv/motorcyle/snowmoble etc. battery, wire and tinder

Chemical Based Fire

1. Matches/fire starters (Yes, this is a chemical fire. Most matches depend on a two part chemical reaction with one half of the chemical on the match head and the other half on the box or book of matches. It is not just a strip of sandpaper! Make sure you pack the striker turned away from the match heads so that it won't accidentally ignite or rub off.

Strike anywhere matches have both chemicals on the tip and when it is struck against a rough surface the two combine to ignite. By the way, a match is the perfect fire starter. It has the ignition source and a small piece of tinder attached. Unfortunately, it is a one-time use and you can only carry so many at a time. Plus, they must be kept absolutely moisture free unless they are dipped in wax or paraffin or are already waterproofed from the factory. Still, keep them dry if at all possible!

2. Potassium Permanganate and glycerin ( Hint: Use a couple of drops of water to accelerate the exothermic reaction) Also note that in very cold temperatures this may not work even if you warm up the elements beforehand. Keep them widely separated if at all possible.

(Potassium Permanganate can be found in the water treatment area of hardware stores and pool stores and glycerin can be found in medical supply stores and pharmacies and has many uses for the outdoorsman as a treatment for insect bites, burn or chafing ointment, treatment for poison ivy, sumac or oak rashes, mild bug repellant, lubricant for a bow drill socket and can be mixed with wood ash to make a simple but effective soap! Truly a multi-purpose item!)

3. Emergency Flare (Even sold in half sizes for carrying convenience)

Whenever you go into the great outdoors, you should always carry at least three kinds of methods of starting fire. Usually, these are a butane lighter, a ferrocerrium rod and matches of some kind. But whatever you choose, make sure that you practice in all types of weather and conditions. Go ahead, challenge yourself, start a fire in the woods in the pouring rain with just one match! It can be done, but requires proper preparation and skill.

Proper Planning When the hunter/gatherer's of yesteryear walked through the wilderness, they did not wait until they arrived at their campsite to gather what is probably the most important material for starting a fire, tinder. As they traveled they were on the lookout for cedar bark, dry grasses, cattail fluff, Canadian thistle down and any other small dry materials that might be needed for fire starting.

You should do the same and carry a spare Ziploc bag for these items in your winter survival kit. The woodsmen of yesterday would protect their hearth, cord and spindle from the elements as carefully as we would our matches today. When Otzi the ice man was discovered in the Otztal Alps in the fall of 1991, he had in his hand a cylinder of birch bark with freshly picked maple leaves and grass, insulating what was a live coal from the elements. He also carried in a clever belt pouch, flint and four pieces of true tinder fungus (Fomes fomentarius) with traces of iron pyrites in their fibers. No iron pyrites were found on or around the site of the discovery, so he must have considered his fire carrying skills equal to the task of the mountain wilderness and the 10,400-foot altitude where he died. Note that he died from a shoulder injury caused by an arrow, not because he was unprepared.

Proper Preparation When preparing to build a fire in a winter survival situation, you must gather your materials first. Gather all the tinder and wood that you need before you start to build the fire.

Tinder may be char cloth, SRO's Mini Inferno, cotton balls, dryer lint, cedar bark fluff, jute twine, sock threads (if they are cotton), small sticks of various sizes etc. Note that larger branches and logs do not need to be cut or split, they may easily be burned in half when the fire is going. Remember winter survival is always a calorie game so don't waste time and energy cutting wood to size.

For ideal winter survival one should probably have a small axe or hatchet to split wet wood and get at the dry inner core, a small saw for cutting large pieces down to size in order to be able to drag them to the fire area and a sharp knife with which to make fuzz sticks. (This is accomplished by shaving small curls of wood left attached to the stick.)

The author has found that it is best to gather a small bundle of sticks from pencil size up to thumb size, dry them out and keep them in a Ziploc bag. Do this when it is not raining, lay them up for a week or so and then pack them with your winter survival kit.

Spark Fire With Cotton Balls and Petroleum Jelly

Also for spark-based fire starting it's hard to beat a cotton ball (make sure it is 100 per cent cotton and not a synthetic) mixed with petroleum jelly and stored in a plastic 35mm film canister. Film canisters can still be had for free at many in-store photo labs. (The petroleum jelly on the cotton balls has many multiple uses including lip balm, soothing galled inner thighs, coating for wind-chapped skin, etc.)

Along with these items, by including a few small sticks of fatwood or greasewood, split small and broken in half, a fire may be started in almost any condition.

Start with the cotton ball (just a piece is needed) drawn out and stretched, then lay two small pieces of fatwood on top, crisscrossed, then lay some pencil thick twigs from your Ziploc bag on top in a tepee fashion and using ferrocerium rod or match etc., apply the spark/fire to the cotton ball. Within short order you will have a small blazing fire.

Of course, in a winter survival situation, you must be careful that the ground on which you build your fire is not too wet. If so, then build a platform of sticks (as dry as possible) upon which to place your fire. If you don't do this, the water and steam from the ground will make it nearly impossible to keep your fire going.

When the fire has reached sufficient strength, then even wet wood may be burned. A fire is like a baby, it must be nursed, nurtured and fed from small to large sticks until it can burn on it's own.

Proper Practice As has already been noted, you must plan and prepare for a proper fire. But, you must also practice, practice, practice! Make sure that you truly own the skill before your life and the lives of those you care about depend on it. This is especially true for all the primitive fire starting methods like the widely touted bow drill.

When you try to start a fire with these methods you will soon learn to appreciate modern fire starters a whole lot more. Along with the practice of making fire, you should practice maintaining fire (of the proper size, a big fire takes a lot of wood, you can get closer to a smaller fire and it is more environmentally friendly, always cook on coals not flame etc.) and practice carrying fire.

Carrying fire could be a lifesaver and was practiced to an art in ancient times. Carrying fire was done by Otzi the ice man and is mentioned in the Biblical Book of Genesis where Abraham carried fire from the base of the mountain to the area of sacrifice. This story dates to somewhere around 2000 to 1500 BC!

The last three areas of winter survival and fire starting are these:

1. The Sure Fire No matter where you find yourself, always carry the ability to start a for sure fire. For some this may be a ferrocerrium rod, for others this may be a lighter, a match, a torch or an emergency flare. Just make sure that if conditions are the worst (Cold, wet, hypothermic etc.) that you can get that fire started.

2. The Next Fire Always think or plan ahead. It is easier to keep a fire going in a winter survival situation than it is to start it again. If you use flint and a steel striker, make sure that you prepare your char cloth in this fire for the next fire. Save some tinder, char cloth, jute twine as well. Dry tinder should be used sparingly as it is one of the hardest items to find in winter.

3. The Last Fire No matter how long you are in a winter survival situation, you should try and keep fire-starting materials for that last ditch fire. Keep at least one match, don't use all the butane in your lighter (They are good on average for about fifty fires or so), save some good tinder and so on. Keep your fire going and practice primitive fire starting methods and save your commercial and irreplaceable fire starters. You never know when you might slip into a creek, get caught in a storm or get overheated and sweaty and need to dry out. The last ditch fire may just save your life!

Put together a winter survival kit

Fire starting in a winter survival situation can be difficult at best. So if you find yourself needing the skills, make sure you own the skills. Plan, prepare and practice. Put together a winter survival kit and pay special attention to your fire starting materials. Go out in your back yard and practice making fire, maintaining fire and carrying fire.

And when you're in that winter survival situation, start that sure fire, keep in mind the next fire and keep something back for the last fire. And with a little help from Above, you'll be back with your loved ones, safe and sound and with a great winter survival story to tell! - by James Bender

This is part 3 of a 4 part Winter Survival series. If you haven't had a chance, check out Winter Survival - Part 1 and Winter Survival - Part 2.

When in a winter survival situation, you might soon realize that you’re not going to get out of the situation you’re in before nightfall. This means you will have to spend the night outside and will need a warm and dry place to sleep.

Whether or not you are an experienced outdoorsman, there is one need that everyone has and that is the need to be sheltered from the weather. Which brings us to another core principle of winter survival.

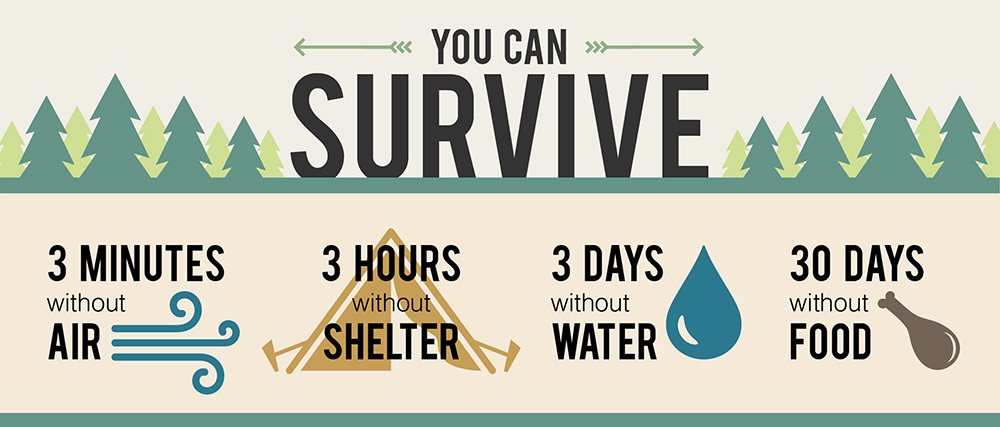

3. If you are to maintain your core temperature and stay dry, you must know how to protect yourself from the elements. As you can see, next to oxygen, shelter is the second highest on the list of priorities. Regardless of why you find yourself in a winter survival situation, you must find a way to provide adequate shelter for yourself and for those who may be with you.

Obviously, the best winter survival shelter is one you don’t have to exert unnecessary energy to build. Such as a cave, a rock shelter, a cabin or trail shelter, even an outhouse built by the forest service are all options that should be considered before expending precious calories to make something in which to shelter.

An ideal winter survival shelter should provide three basic needs:

A. It must shelter you from the wind.

B. It should shelter you from precipitation.

C. It must provide some insulation from the cold.

So, with these in mind, the next main principle of winter survival is this:

4. It's easier to take shelter than to make shelter, or it's easier to take some form of a shelter than to make a whole shelter. If you cannot find a natural or man-made shelter in which to spend the night in or wait out a coming storm, you must make one. If you are new to self-reliance you may think that a tent is an ideal way to take shelter with you, but very few people are going to bring a tent along with them everywhere they go. And even if you have a tent, it only provides two of the three basic needs. It will shelter you from wind and precipitation but provides little if any insulation from the cold and you cannot have a fire close enough to feel the heat without endangering the fabric of the tent.

Normally, a tent is used in conjunction with a sleeping bag of the proper temperature rating for the environment it is to be used in. The sleeping bag is what provides insulation from the cold. But, if you have a tent and a winter rated sleeping bag, it's not winter survival -- you're just camping! The real question is what do you do when you find yourself needing warmth and shelter that is not readily available?

The best shelter to take and make is the composite lean-to shelter. It consists of very small, lightweight, and portable components carried in a small winter survival kit that can be placed in a pocket or pack when needed.

When in a winter survival situation, you can build the composite shelter one of two ways, either in a lean-to or an A-frame style shelter. The typical lean-to shelter is not an adequate winter survival shelter because it is open to the elements of wind and rain on three sides and is not insulated. The typical A-frame/tent style shelter does a better job at shedding water and shielding from the wind but is still open on the two ends and doesn't allow as much exposure to your fire and is not well insulated. The composite lean-to shelter uses the same configuration as a standard lean-to with an insulated top and sides and partially blocked front. To build an insulated lean-to shelter you will need the following items.

If using a mylar survival blanket it can be unfolded and used as is. When using a drum liner/garbage bags they must be slit with a knife along the two long sides and duck taped together lengthwise. The advantage of mylar for winter survival is that it reflects heat back to your body from your body and from the fire.

The advantage of the garbage bag is that it can be used as a poncho, to gather debris for insulation, a makeshift hobo pack sack or stuffed with leaves as a ground mat. A heavy-duty garbage bag is truly a multi-purpose survival item. The best idea is to have two garbage bags and one mylar survival blanket as well, but this is winter survival and you have to choose what to bring, as you can't carry everything.

Insulating Your Shelter

To insulate your shelter, pile leaves and debris on top of the sheeting (being sure not to puncture it) to a depth of six to eight inches. To keep the debris from blowing away, pile several branches on top of the debris. Next, cut small poles of the proper length to match the grade on the sides of the lean-to. Sharpen the bottom of the poles and drive them into the ground on the sides of your shelter approximately six to eight inches apart.

Then, do the same to the front of the shelter from one end to approximately two thirds of the way across. Weave small flexible limbs in and out of the poles on both the sides and the front of the shelter making a loose mat. If you can find them, pine branches work best for weaving. Pile debris against the sides and lay sticks on it to keep the debris from blowing away.

The front should not have debris piled against it as this is toward your fire and you don't want to create a dangerous situation for yourself by piling a giant tinder bundle in front of your shelter. Try to make the front weave as tight as you can, using green pine branches if possible. On the inside of your shelter, pile leaves and debris or small pine branches several inches thick to lie on. Now after your fire is built you can crawl in and enjoy!

Constructing An A-Frame Shelter

The A-frame composite shelter is built much the same way except that it doesn't need two trees to start with. To build an A-frame shelter you will need two heavy sticks approximately four feet tall lashed together at the top and spread apart to form an "X" and one long ridgepole approximately eight to ten feet long set in the top of the "X" and placed at an angle to the ground and lashed to the two front poles. Then, more poles are laid along the ridge vertically from top to bottom on both sides.

Lay the mylar/plastic sheeting across the top of the ridge, wrap a smooth stone (Or a bobber) in each corner, tie around it with cord and stretch it to the ground and tie it to a wooden peg. The bobbers are uniform and smooth keep the plastic/mylar corners from ripping. (You can use smooth pebbles or stones instead of bobbers but they never seem to be around when you need them.)

Then begin to pile debris to a depth of six or eight inches starting at the bottom and going the top again taking care not to puncture the sheeting. Lay branches on the top to keep the debris from shifting or blowing away. Pile debris on the floor to the proper thickness for a sleeping mat and slide in feet first and get comfortable.

Important Shelter Tips

Note: In either shelter you should add to the debris on the floor every day or replace it as it will definitely crush down from laying on it and will begin to lose some of its insulating properties. Make sure that your shelter is not in an area that could flood (look for flood litter height in the bushes and trees around you), make sure it's not underneath any large, dead branches that could fall on you; called “widowmakers,” and ideally it should be about halfway up a slope as the top of a ridge is windy and the bottom of a gully is where cold air condenses and settles. Dig a shallow trench around your shelter to divert water and place your fire a safe but "feelable" distance from the front of it. Make sure to stop and make camp at least two hours before dusk, as you should be able to make the composite shelter in this amount of time.

You may never find yourself in a winter survival situation, but if you do, it's good to take the basic materials to make a proper shelter. Sure, many people can make shelter without a knife, cord or sheeting, but the author believes that a little preparation goes a long way! After all, when you get a shelter built and a warm mat to sleep on with a blazing fire out front, it's not winter survival any more. Now, you're camping! - by James Bender

In the last article about winter survival, we conveyed the necessity of being properly dressed for a survival emergency. Read Winter Survival - Part One. In Part Two of this series we want to address another universal principle of winter survival.

Principals of Winter Survival 1. It's easier to stay warm and dry than it is to get warm and dry.

Picture the scenario: It's December and you're heading out to be with family for the Christmas holiday season. The car is loaded with gifts. Also, you are loaded down with clothes, shoes and accessories for Christmas parties, church services, etc. Your car has just slid off the road into the ditch. It’s raining/sleeting/snowing and the weather report indicates it's going to get worse, much worse, over the next several days. There's no other traffic as most people are staying home. There's little to no cell phone signal, so calling a tow truck is not an option.

Like so many of us, who travel from point A to point B during the winter, the beginning and end of the journey is filled with warmth, light, friends and family. But, what we often fail to consider are the many miles of relatively empty, wooded, mountainous or just open terrain in between.

When faced with a winter survival situation, staying in your car is not necessarily the best option. Your car is a big metal object with poor insulation qualities, and there is only so much fuel in the gas tank. Staying near your car is a better option if there is enough wood for a fire and a place where you can shelter from the storm.

Emergencies require us to make choices. Do you stay in the car, running the engine for about ten minutes every hour to run the heater until the gas runs out or do you find a place close to your vehicle where you can (hopefully) start a fire and build a shelter? Or, do you do both, staying in your car until the storm is over and then seek better shelter?

Let’s continue the scenario: You know that your car is the first thing that rescuers will find after you are missed and a search is initiated. So, making a decision, you wait until a lull in the storm, you get out of your car, (You did remember to dress to survive, didn't you?) open the trunk, dig past the presents to get your winter survival kit out, then leaving a note for your rescuers, you head to the nearest wooded area to find a windbreak and begin to prepare your shelter and get a fire started. (Note: If this scenario seems implausible the author would encourage you to read the tragic winter survival story of James Kim and his family traveling from Seattle, Washington to their home in San Francisco, California after the Thanksgiving holiday in 2006.)

Avoid hypothermia

The number one killer of people in the outdoors is hypothermia. This is where your body's core temperature drops below 95 degrees Fahrenheit or 35 degrees Celsius. There are four stages of hypothermia and they are listed as mild, moderate, severe and profound. Needless to say, in a winter survival scenario, you want to avoid all four. Any stage of hypothermia is potentially dangerous and may bring great discomfort and suffering or even death.

Although hypothermia can be caused by several factors, being wet in a winter survival situation truly complicates the problems that the survivor faces. The key is to avoid getting wet if at all possible. If you can stay dry, it is much easier to stay warm, as your body will naturally generate heat from body fat and calories consumed. Stay sheltered in your car, under a ledge or overhang or under a large coniferous tree. Use whatever you have at hand to keep dry.

Outside of precipitation, one of your biggest enemies in winter survival is perspiration. Wet clothing will remove heat from your body approximately 25 times faster than dry clothing. Whatever you do, whether shelter building, fire starting or just walking/hiking, don't allow yourself to begin to sweat. Sweating lowers your core temperature (as its designed to do), causes you to lose precious water from your body and makes your inner layer(s) of clothing wet. (Remember, it's easier to stay warm and dry than it is to get warm and dry.)

Sometimes people will argue about what you need to do first in a winter survival situation. Do you start a fire or do you build a shelter? The answer is that it depends on your situation. If it is cold but dry, then a fire is what you would build first, but if there is any chance of precipitation, then the choice would be to build a shelter.

From experience, the author can affirm that it takes a long time to dry clothes by an outside fire during the winter. Also, having experienced mild to moderate hypothermia, he can also affirm that it is much easier to stay dry than to try to get dry. Fortunately, in our situation we had a backpack with dry clothes, a propane backpacking stove, water in a canteen and hot chocolate in a pouch, which took very little time to prepare. (Note: Hot chocolate is a better drink in winter survival than hot tea or coffee. Tea and coffee are diuretics and will make you lose water faster. Water is just as important in the winter as it is in the summer because it is a catalyst in metabolizing fat and digesting food to keep you warm. Also, hot chocolate is better because the fat content will help you stay warm.) Even with the dry clothes and hot chocolate, it took the better part of an hour before the symptoms of hypothermia went away.

So, if you find yourself in a winter survival situation, don't allow yourself to get wet. Take steps to guard against the weather outside and also to ensure that you don't heat up too much from the inside. And remember, a little preparation and planning go a long way. If at all possible, it's best to avoid being in a winter survival situation in the first place! - by James Bender

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed